Today Me, Tomorrow You 👀

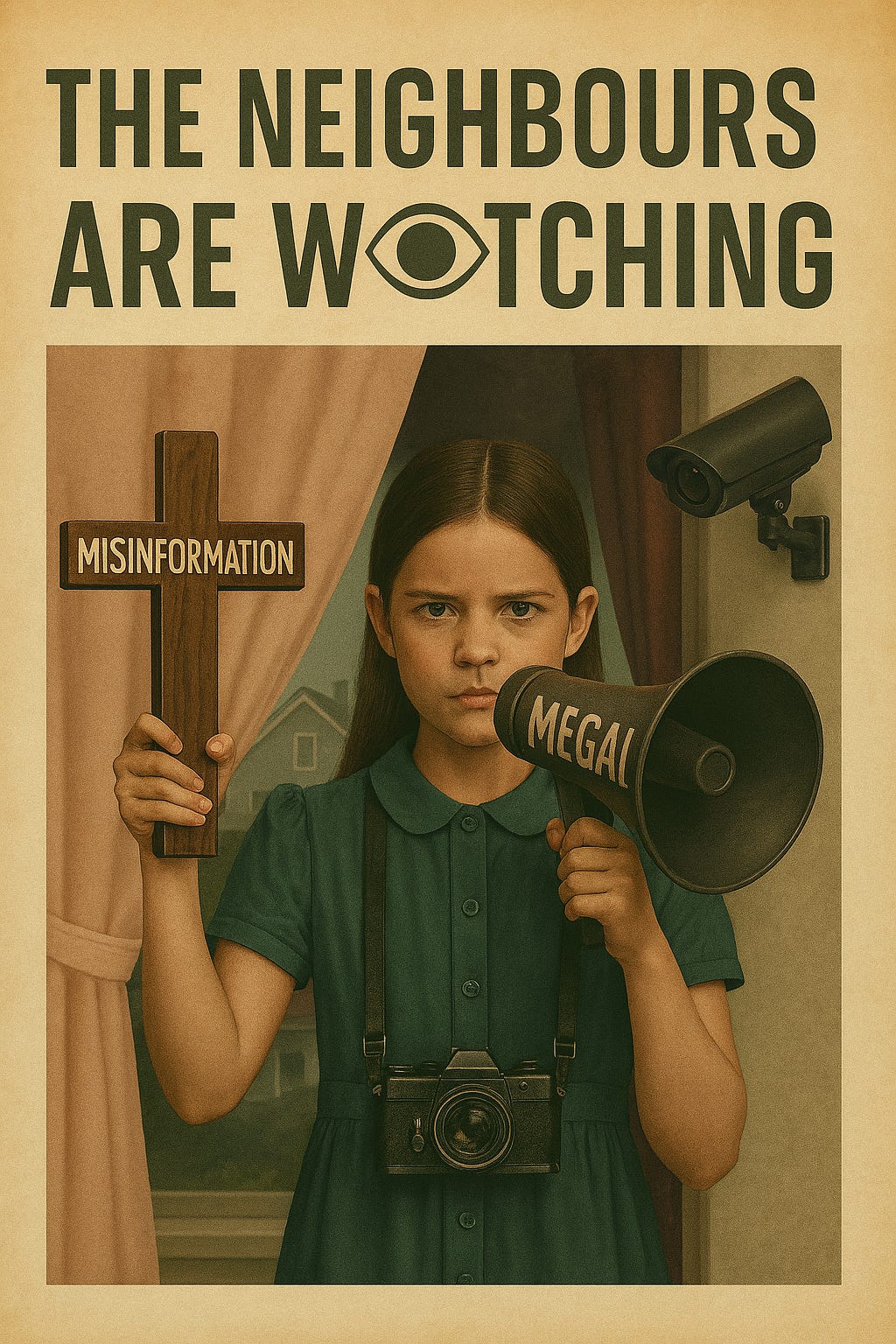

From village gossip to cancel culture.

One of the first things you learn in childhood is the rules that are supposed to keep the world from falling apart. Be kind. Tell the truth. Brush your teeth. Little commandments for little people. And right alongside them, in my house, came another one — softer, but no less binding: care what the neighbours think.

At the time, it sounded simple, even noble. My parents weren’t schemers or manipulators; they weren’t playing sick power games. They were modest Christians, and for them, this wasn’t about image; it was about decency. Love thy neighbour, live in harmony, don’t bring unnecessary scandal to the family. It was the everyday version of biblical goodness, baked into village life: people watching out for each other, keeping one another honest and close. And when your neighbours were decent too, it worked beautifully. It kept the peace. It stitched the social fabric together.

But the thing about rules is that they only work if everyone is playing the same game. And sooner or later, you discover the neighbour who isn’t. The one who doesn’t care about decency, only about gossip. The one who learns how to weaponise your politeness, how to twist your goodwill into their own leverage. And suddenly the whole system flips: what felt like community turns into surveillance, what felt like belonging turns into performance. You’re still following the rules, but the rules don’t protect you anymore — they expose you.

That’s the moment the penny drops. You realise that “what the neighbours think” can be the softest form of tyranny, because you don’t need bars on windows if people are already policing themselves. And once you see that, it’s impossible not to recognise its modern reincarnation: what we now call cancel culture.

And how does it feel? Like walking on eggshells barefoot, except the eggshells are wired to a loudspeaker. Like losing gravity — one moment you’re fine, the next you’re falling, and by the time you ask what happened, you’ve already hit the ground. And sometimes it feels like bad theatre, absurd comedy. Everyone knows the “reason” is flimsy, but it gets dressed up in the serious language of reputational risk, community standards and brand values. It’s like someone cancelling Thanksgiving because the turkey looked at them funny, but the cancellation notice is printed on embossed letterhead.

Why is it done? Because power never wastes a good rumour. Corporations cancel to protect themselves, governments cancel to shut people up, communities cancel to show off their virtue, and neighbours cancel because nothing feels better than saying, “Did you hear…?” There’s always a payoff. Cancel culture is a vending machine for power; you just have to know what number to press.

And you don’t even need to exaggerate. Jimmy Kimmel played a clip of Trump bungling a death announcement — suspended. Stephen Colbert cracked a joke during a merger — retired. Meanwhile, Brian Kilmeade, smiling on breakfast television, says, “Just kill ’em… involuntary lethal injections,” and he’s still on air, still paid, still serving up pancakes. The rule is simple: cruelty is fine; crossing the powerful is not.

And the absurdity of the reasons? Endless. A teacher loses her job because she reminded her students of the actual words Charlie Kirk once said. A man goes viral because his cat sat on a newspaper photo of the President, and suddenly, he’s branded disloyal.

A book club dissolves into a tribunal because one member suggested 1984 might lose its edge if you edited it into a beach romance. A journalist publishes an exposé on corruption and doesn’t just lose her job — her bank account freezes, her family is harassed, and her name disappears from the internet like she never existed. It’s serious, it’s absurd, it’s dangerous, but it’s not original. Every flavour tastes the same in the end — like fear.

And here’s the cruellest part: it works because we know it can happen to anyone. Heute ich, morgen du. Today me, tomorrow you. The circus only works because we’re all afraid to be next. People say, “They deserved it,” until it’s their turn. And in the meantime, everyone gets smaller, quieter, and less honest. People start cancelling themselves before anyone else has to bother.

And yet it doesn’t stop. Because the fuel is gossip, and gossip never runs out. Gossip is renewable energy. You can whisper it, you can screenshot it, you can hashtag it, and the machine keeps humming. Corporations love it because it saves them money, governments love it because it shuts people up, and neighbours love it because it makes them feel powerful. The only people who don’t love it are the ones caught in its teeth, and by then it’s too late — heute ich, morgen du.

And it makes me wonder: what does it do to a society when everyone is terrified of being the next one chewed up? You get smaller. You censor yourself. You police your own jokes. You start second-guessing your own thoughts, like, “Can I even think this, or will my smartphone blink at me?” And the punchline is: you don’t even need the government anymore. People cancel themselves pre-emptively. They carry the neighbour inside their head. And that is the ultimate victory of the system. It doesn’t need to police you anymore. You police yourself. You are the neighbour, peeking through your own curtains, whispering your own fears into your own ear. The prison is built, and you hold the key.

Today me, tomorrow you.