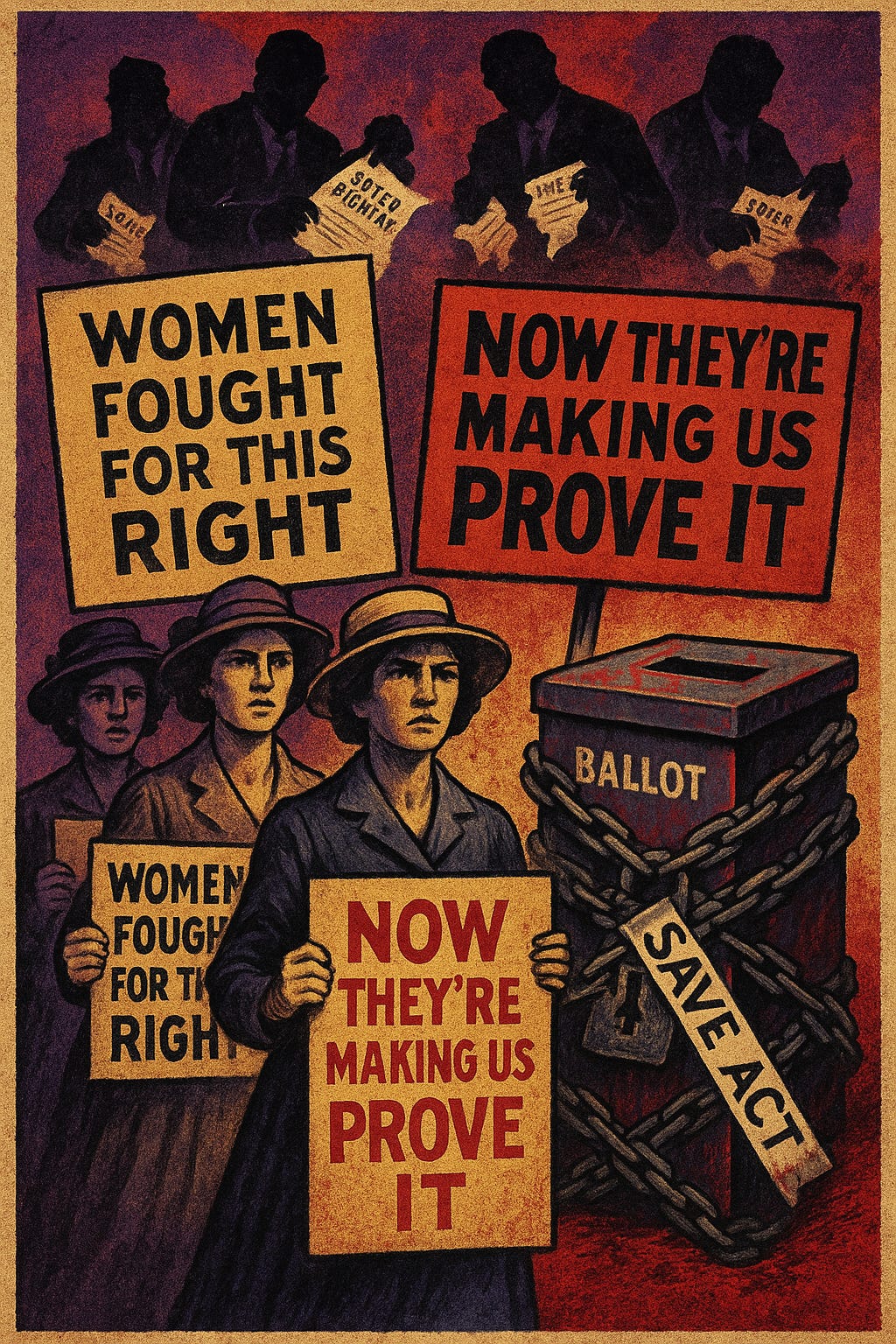

Understanding the SAVE Act and Its Impact on Women’s Voting Rights

An investigation into how citizenship documentation laws could disproportionately impact women — especially those who’ve changed their names.

What Is the SAVE Act?

The Safeguard American Voter Eligibility (SAVE) Act is a proposed federal law that would impose new requirements for voter registration in the United States. Introduced by Republicans (originally by Rep. Chip Roy and backed by figures like House Speaker Mike Johnson), the SAVE Act would require anyone registering to vote in a federal election to provide documentary proof of U.S. citizenship (DPOC). In simpler terms, instead of just signing a form affirming you are a citizen (as is the case now under the National Voter Registration Act), you would have to show specific documents (like a passport or birth certificate) before you could get on the voter rolls. The House of Representatives passed this bill in 2024, largely along party lines, but it stalled in the Senate. It has since been reintroduced and remains a priority for its supporters, meaning it could resurface in future elections or legislative sessions.

How Would the SAVE Act Change Voter Registration?

Under current federal law, eligible voters can register by providing basic information and affirming their citizenship under penalty of perjury. The SAVE Act, however, mandates that states require physical proof of U.S. citizenship for voter registration. Acceptable documents listed in the bill include a U.S. passport, naturalisation certificate, enhanced state ID or driver’s license noting citizenship, or a combination of birth certificate plus a government photo ID, among others. In practice, this means:

If you have a valid passport, that alone would satisfy the requirement (since a passport proves both your identity and citizenship)

If you don’t have a passport, you might use a birth certificate to prove citizenship, but you’d also need a government-issued photo ID (like a driver’s license or state ID) that matches the information on that birth certificate. Simply having a birth certificate alone isn’t enough – the name and details on it must align with your current identity documents.

Other proofs, like a military ID plus service record showing U.S. birthplace, or certain tribal or naturalisation documents, are also listed.

Furthermore, the bill would require these documents to be presented in person. It wouldn’t allow one to simply mail in a voter registration form or register online without showing original documents. For example, states could no longer accept a federal mail-in registration form without the applicant showing up at an election office with their papers. This is a significant change from the status quo and would make registering to vote more like the process of getting a REAL ID driver’s license or a passport – a process that can be cumbersome for many people.

The strictness of the SAVE Act is unprecedented. Voting rights experts note that it would be “the most severe voter identification or proof of citizenship law in the nation,” going even beyond the strict law Arizona tried (and was repeatedly blocked in court). In other words, no state currently has requirements as tough as what the SAVE Act proposes. States would have just 30 days to implement these new rules, with no additional funding provided for the mandate. The law even creates penalties for election workers: if a clerk registers someone without the proper citizenship proof, they could face fines or even jail time. It also includes a “private right of action,” meaning any ordinary citizen could potentially sue an election official whom they believe registered a voter without the correct documents. This creates a strong pressure on officials to be extremely strict in verifying papers.

Why Are Women Disproportionately Affected?

On the surface, the SAVE Act’s rules apply to everyone. In reality, however, women – especially those who have changed their names after marriage or divorce – would face a significantly heavier burden to register or to update their voter registration. This is because the name on a person’s primary citizenship document (often a birth certificate) may not match their current legal name. Here’s why that matters:

Name Changes After Marriage: The vast majority of women who marry in the U.S. adopt their spouse’s last name. A Pew Research survey found around 79% of married women in opposite-sex marriages took their husband’s surname, whereas very few men (only about 5%) changed their name. This means most married women’s birth certificates (and possibly other documents like a naturalisation certificate, if they’re naturalised) no longer display their last name. For example, a woman born as Jane Smith who is now legally Jane Doe after marriage has a mismatch between her birth certificate (Smith) and her driver’s license or other ID (Doe). Under the SAVE Act, this mismatch becomes a hurdle. She couldn’t simply show her ID and birth certificate and register – because an election official might say, “These names don’t match. How do we know you are the same person as on the birth certificate?” In effect, a marriage license or other proof of name change would also be required to bridge the gap. The law doesn’t explicitly list marriage certificates as approved documents, but it does instruct states to set up a process for handling discrepancies due to name changes. Critics worry this guidance is too vague, and states might handle it inconsistently. The bottom line is that women who changed their names must produce additional paperwork to vote – an extra step that men (who usually have the same name their whole lives) are far less likely to face.

“Maiden Name to Married Name” – a documentation trail: For a woman who took her spouse’s name, registering to vote would likely require multiple documents presented together. Using the example above, Jane (Smith) Doe would need: 1) her birth certificate showing the name Jane Smith (proving U.S. birth/citizenship), 2) a current photo ID (say a driver’s license) showing the name Jane Doe, and 3) her marriage certificate showing that she legally changed her name from Smith to Doe on a certain date. Only by cross-checking all three can an election official confirm that Jane Doe is the same person as the citizen born as Jane Smith. If any of those documents are missing or if the woman hasn’t kept them handy, her registration could be rejected or delayed until she provides them. This is why some have dubbed the proposal a “marriage penalty” for voting – it doesn’t literally penalise marriage, but it penalises the act of changing one’s name, something predominantly done by women.

Divorced or Multiple Name Changes: Now consider women who have not only married but later divorced or remarried. Many women retain their married name after divorce, especially if they have children or built a professional identity with that name. Others may revert to their maiden name or even take a new name. In any case, each name change adds another link in the documentation chain. For instance, suppose Susan Johnson marries and becomes Susan Miller, then divorces and goes back to Susan Johnson. If she wants to register to vote under Susan Johnson (her current name), her birth certificate might say Susan Johnson (if that was her maiden name originally, she’s in luck there), but if she had changed it to Miller legally and then back, she might need to show the marriage certificate (Johnson → Miller) and the divorce decree or name change order (Miller → Johnson) to account for the switch back. If she instead kept the name Miller after divorce, then her current ID says Miller while her birth certificate says Johnson – she’d need the marriage certificate to connect them. For women who have married and divorced multiple times, the paperwork requirements multiply accordingly. They would have to save perhaps decades-old documents (marriage licenses, divorce decrees, legal name change orders) and present possibly several of them just to verify citizenship and identity for voting. Losing one of those papers or not having it readily available could jeopardise their voter registration. This burden again falls mainly on women, since they are far more likely to have multiple names over their lifetime.

Transgender Women and Others with Name Changes: It’s not only marriage or divorce that can cause someone’s legal name to differ from their birth record. Transgender individuals, for example, often change their first name (and sometimes last name) as part of affirming their identity. If a trans woman was born with the name given at birth that she no longer uses, her birth certificate might not match her current ID. Many trans people do legally change their names through a court process, meaning they’d have a court order document similar to a divorce or marriage certificate to show the name change. However, navigating this under the SAVE Act could be difficult. If a state official is unfamiliar or unsympathetic, they might question the documents more stringently. Additionally, some states make it hard to update birth certificates or IDs for trans individuals, which could result in a situation where a trans woman’s ID and citizenship documents are inconsistent. She, like a married woman, would face the hurdle of proving “Yes, I am the same person as this document, here’s the proof.” While the SAVE Act’s text doesn’t single out transgender people, anyone who has changed their name for any reason will face extra scrutiny – again, a group in which women (including trans women) are a majority because of the prevalence of marriage-related name changes.

Women without Ready Access to Documents: Apart from name changes, consider other scenarios common to women. Older women may have been born at a time or place where they never obtained an official birth certificate, or they may simply not have it anymore. For example, some older voters (men and women) were born with midwives or at home and might not have standard birth records. Women in rural areas or women with limited income might never have applied for a passport (which costs over $100) and might find it challenging to take time off to go to a government office with documents. Naturalised citizen women (immigrants who became U.S. citizens) do have citizenship papers, but if they changed their name either at naturalisation or afterwards through marriage, they’d face similar issues. The Brennan Center for Justice estimates that 21 million U.S. citizens of voting age (about 9%) do not have easy access to documents proving their citizenship. A significant number of these are women, in part due to the name-change factor. In fact, one survey by the Brennan Center found that approximately 34% of voting-age women have proof-of-citizenship documents that do not display their current name, meaning about a third of women would immediately run into the name mismatch problem under the SAVE Act. This figure highlights how pervasive the issue is. By comparison, almost all men have the same name from birth throughout life, so they’re far more likely to have a birth certificate and ID that match up.

In short, because of traditional naming conventions and life events, women as a group are poised to experience the most trouble under the SAVE Act’s requirements. Married women (and women who were married in the past) are front and center. Even the bill’s supporters have effectively acknowledged this. Cleta Mitchell, a conservative lawyer who advocates for the bill, admitted that the process “is a pain” but noted that “millions of women do it every day” in other contexts (like updating Social Security or bank accounts after a name change). Voting rights advocates respond that making something hard on millions of people is precisely the problem. Yes, women can gather up a marriage license, birth certificate, and ID, but many may be discouraged or tripped up by the hurdle. It’s an added layer of bureaucracy that will inevitably result in eligible women being turned away or giving up on registering. Indeed, the National Organization for Women noted that roughly 90% of married women have a different last name on their government ID than on their birth certificate, and as many as one in three women could be rejected at the polls unless they present additional documents to reconcile that difference.

A Step-by-Step Example: From Marriage to the Ballot Box

To make the impact clearer, let’s walk through a hypothetical scenario under the SAVE Act:

Step 1: Gathering Citizenship Documents: Maria Gonzalez is a U.S. citizen by birth, but after marrying, she goes by Maria Ramirez. To register to vote under the SAVE Act, Maria first needs proof that she’s a citizen. She doesn’t have a passport (like about half of Americans), so she plans to use her U.S. birth certificate. She digs it out of storage – it shows the name Maria Gonzalez and her place of birth in California.

Step 2: Photo ID: The law also requires a government-issued photo ID. Maria has a driver’s license, but it’s in her married name, Maria Ramirez. She now realises her ID name (Ramirez) and birth name (Gonzalez) don’t match. If she shows these as-is, the election official will not be able to confirm she’s the same person – the paperwork could be rejected.

Step 3: Linking the Names: To resolve this, Maria must provide proof of her name change. She finds her marriage certificate from when she married her husband, which shows that Maria Gonzalez married Juan Ramirez on a certain date, and that she chose to take the last name Ramirez. This marriage license is the crucial link showing that the person named Gonzalez is now the person named Ramirez.

Step 4: Presenting in Person: Under the SAVE Act, Maria can’t just mail these documents in; she needs to go in person to her local election office (or other designated site) to show them. She may need to take time off work or find transportation to do this. She brings her birth certificate, driver’s license, and marriage certificate. At the counter, she hands these over and the official inspects each one. The official is cautious, knowing they could be penalised if they register someone without proper proof. They verify that the birth certificate is an original or certified copy with a state seal (photocopies aren’t accepted). They compare the name and birth date on it to the marriage certificate, confirming that Gonzalez became Ramirez. They then check that the driver’s license photo matches Maria herself and that the name matches Ramirez.

Step 5: Registration Outcome: If everything is in order, Maria’s registration is processed, and she’s added to the voter rolls. If any piece is missing or questionable – say Maria couldn’t find her marriage certificate, or the birth certificate was a photocopy, or if there was a typo or discrepancy (e.g., the marriage license had a slightly different name spelling) – her registration could be denied or deferred until she fixes the issue. For many women, these hurdles could mean delays, extra expenses, or not registering at all. Consider that some might have to pay for new copies of marriage licenses or court documents, which can cost money and time waiting for mail; others might simply be confused by the requirements if instructions aren’t clear (especially if English isn’t their first language, or if they have limited literacy). The process is more complex than what men typically face, because a man named John Smith can likely walk in with his birth certificate for John Smith and his ID for John Smith and be done. A woman who changed her name has to carry the equivalent of an entire paper trail of her life events to exercise the same right to vote.

What Supporters Say vs. What Critics Warn

Supporters of the SAVE Act, including its Republican authors, argue that these measures are necessary to prevent non-citizens from illegally voting in U.S. elections. They often point to the importance of election integrity and claim (without solid evidence) that there are significant numbers of non-citizens attempting to register and vote. President Trump, for instance, has falsely alleged that thousands of illegal votes are being added, and proponents see documentary proof as a safeguard. The idea is that by forcing everyone to show papers, it closes any “loophole” where someone who isn’t a citizen might slip through by just attesting to citizenship. They compare it to needing ID or paperwork for other privileges, like getting on an aeroplane or obtaining government benefits, and say voting should be treated with the same level of security.

Critics, however, point out a few key realities:

First, impersonation or fraudulent voting by non-citizens is exceedingly rare. Studies and investigations have repeatedly found that such cases are virtually statistical zero. For example, one analysis found only 30 suspected non-citizen votes out of 23.5 million votes in a recent election – that’s about 0.0001%. In short, there is no evidence of any significant number of non-citizens voting, let alone swinging elections. Strong penalties (felonies) already deter non-citizens from attempting to vote, and election officials do have checks in place (like verifying Social Security numbers or other data). The SAVE Act is seen as a “solution in search of a problem,” one that doesn’t exist in any meaningful way.

Second, the burdens of this law fall on legitimate voters – overwhelmingly women, as we’ve discussed, as well as seniors, young people, and minorities. Voting rights groups like the Brennan Center and League of Women Voters warn that millions of eligible Americans could find it harder to register. Those without passports would have to navigate documentation challenges that might discourage participation. The law would especially impact longtime women voters who have moved or need to update their registrations (perhaps due to a name change or address change). Even if they’ve voted for decades, a change of address under the SAVE Act would force them to show up with papers in hand or else they get purged from the rolls.

Third, critics emphasise the discriminatory impact. Because women are the most likely to have a name mismatch issue, some have characterised the SAVE Act as part of a broader “war on women” in politics. It’s not overtly written as a gender law, but in effect, it could disproportionately disqualify or sideline women voters. During debate on the bill, amendments were proposed to make exceptions or accommodations (for example, to explicitly accept a marriage certificate as proof of name change, or to provide waivers for older voters), but reports indicate that those amendments were rejected, signaling that the bill’s backers were not keen on easing the requirements. The strict stance suggests that the difficulty is the point – i.e., creating friction in the registration process, which historically reduces turnout among those who face the most hurdles.

Finally, opponents note that election officials themselves might overzealously enforce the law out of fear. The SAVE Act threatens fines and prison for officials who make an error, and even allows others to sue them. This could lead to officials being extremely strict, possibly rejecting perfectly valid documents just to be safe. A slight discrepancy (like a middle name or a hyphen in a name) might become grounds for refusal if the law isn’t crystal clear. The bill does say states “shall establish a process” for people to provide additional documentation for name discrepancies, but it leaves the details up to each state. Voting rights experts worry that some states might set up onerous procedures or that local officials will be confused about what’s acceptable. For example, would a woman’s marriage certificate definitely be accepted everywhere? The bill doesn’t explicitly list it, so some bureaucrat might say, “Sorry, we need a court-issued name change document” (even though a marriage license is a legal name change in most places). This uncertainty could lead to inconsistent treatment from state to state, or even county to county. In short, critics see the SAVE Act as a voter suppression tool, one that uses the guise of citizenship verification to target groups that historically face more paperwork obstacles, with women at the forefront of those groups.

The Bigger Picture: Women’s Rights and the Current Climate

The SAVE Act does not exist in a vacuum. It forms part of a broader pattern of legislative and political efforts that many view as aimed at curbing women’s rights and autonomy in the United States. Its impact on voting rights intersects with a wider rollback of protections in areas such as reproductive freedom and marital independence.

Reproductive Rights: Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, several states have enacted strict abortion bans, significantly reducing women’s control over their reproductive choices. In this shifting landscape, control over bodily autonomy has increasingly moved from individuals to state legislatures, often dominated by male lawmakers. Future national abortion restrictions and even potential threats to contraception access have been openly discussed. Within this context, the SAVE Act plays a reinforcing role: by making it more difficult to vote, particularly for younger, unmarried women who are disproportionately affected by these policies, it could undermine efforts to resist or reverse such changes through the ballot box. Diminished political power often leads to diminished rights elsewhere.

Divorce and Financial Independence: Although the SAVE Act focuses solely on voter registration and has no direct connection to marriage laws, it coincides with another concerning trend: renewed political interest in rolling back no-fault divorce laws. No-fault divorce, available in all 50 states, allows couples to dissolve their marriages without proving wrongdoing. Critics—mostly from conservative circles in states like Louisiana, Texas, Oklahoma, and Nebraska—have begun to argue for its repeal, claiming that it enables individuals (often women, in their view) to leave marriages too easily.

Rolling back no-fault divorce could have serious consequences, particularly for women. Before its introduction in the 1970s, women often needed to prove adultery, abuse, or abandonment in court to be granted a divorce. If they couldn’t, they remained legally bound to their husbands, unable to remarry or claim a fair share of marital assets. In effect, men could block divorce proceedings and deny financial equity, leaving women trapped. Studies have shown that the implementation of no-fault divorce laws was associated with declines in domestic violence and suicide rates among women, suggesting that the ability to leave harmful marriages has had a profound impact on women’s safety and freedom.

While marriage and divorce laws are state-governed, the fact that high-profile figures—including elected officials and media personalities—have entertained the idea of limiting or reversing no-fault divorce is alarming to many. It signals a willingness to revisit an era when women had far fewer rights over their lives, finances, and futures.

When placed alongside proposals like the SAVE Act and ongoing attacks on reproductive rights, these developments reflect a larger movement to curtail women’s political, physical, and economic agency. The SAVE Act, in particular, targets access to democratic participation. If women face greater hurdles in registering to vote, their ability to influence the very laws that govern their lives is weakened, further entrenching policies that do not reflect their needs or values.

Why It Matters

The SAVE Act might sound like a dry election law, but it carries real human implications, particularly for women. It would turn a commonplace life choice (changing one’s name after marriage or divorce) into a potential barrier to exercising one’s fundamental right to vote. Millions of women could find themselves scrambling for documents or navigating government bureaucracy just to remain voters in good standing. The women most affected would include those who are married, divorced, or widowed, as well as many others who have changed their names or lack current documents. It’s not an exaggeration to say that without the right paperwork, a woman who’s been voting for 40 years could be told she’s no longer eligible–until she produces a marriage certificate from 1975, for example. This is why observers describe the act as having a disenfranchising effect on women voters.

It’s also important to recognise that laws like this don’t emerge in a vacuum. The SAVE Act is one piece of a larger puzzle in which women’s rights – be it the right to control their own bodies, to leave an untenable marriage, or to cast a ballot – are being politically contested. Whether or not the SAVE Act becomes law, the fact that it was pursued at the highest levels of government signals a willingness to undermine democratic participation under the guise of “integrity”. For women, especially, it’s a reminder that gains of the last decades (from voting access to personal freedoms) should not be taken for granted. Staying informed and engaged on these issues is crucial.

In summary, the SAVE Act would mean a step backwards for women’s voting rights. It imposes new hoops to jump through that would mostly ensnare women who have married or divorced, effectively punishing them for life choices that our society has long accepted. When combined with other efforts that limit women’s autonomy, it paints a grim picture, as the user suspected. The best way to guard against such changes is to spread awareness, exactly by breaking down the law as we’ve done here – so that all citizens, women and men alike, understand what’s at stake and can respond through advocacy, voting (while we still can easily), and speaking out. Policies like the SAVE Act demonstrate how legal barriers can quietly erode rights, and why vigilance is needed to protect the progress women have made in American society.

Another fantastic educational read outlining more of the cheap tactics being used by the current cheap regime to potentially make America even more undemocratic.